Warwick Goldsmith - Laying down the law

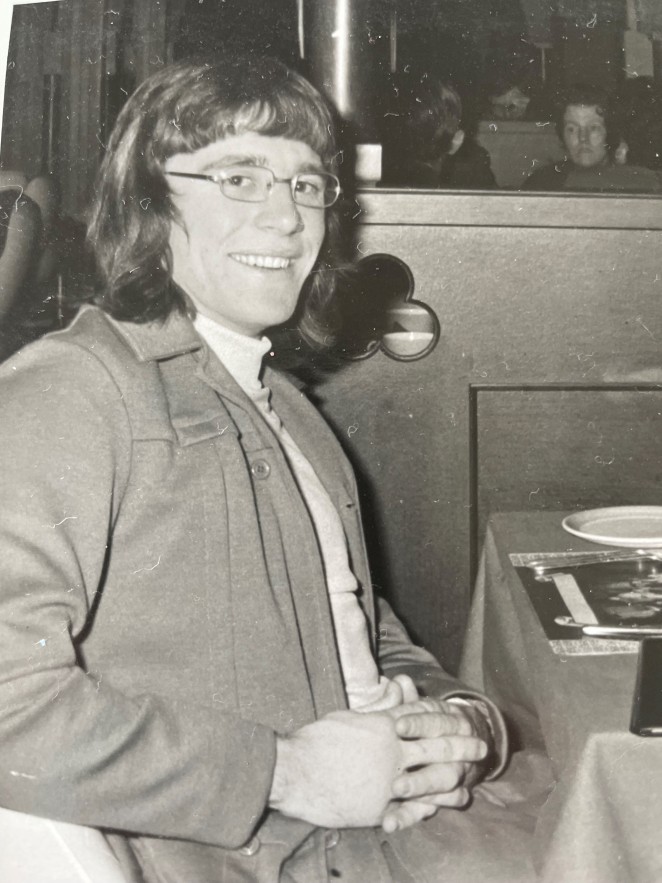

He arrived in Queenstown in 1982, a long-haired, well-travelled, jobless Auckland law graduate, fronting up to a notoriously scary southern judge.

Within 10 years longtime Queenstown lawyer Warwick Goldsmith was leading some of the Queenstown Lakes District Council’s most influential decisions as a councillor, then chairman of its planning committee.

During that time the council faced the huge upheaval of a new Resource Management Act in 1991. “No one knew what they were doing,” he says. “The government just passed a law and we had no guidance, so we made it up as we went along.”

As a lawyer specialising in planning and development, Warwick played a lead role in consenting key developments like Lake Hayes Estate and Shotover Country, the Millennium and Heritage Hotels, Jack’s Point and Bridesdale subdivision.

After a stint chairing the Queenstown Film Society, Warwick chaired Queenstown’s Art Centre Trust, battling unsuccessfully for five years to get an Arts Centre off the ground. He also chaired an informal social services housing group.

Chairing the District Waterways Authority, he worked with harbourmaster Marty Black, under Mayor David Bradford. “David was a good mayor as he delegated,” Warwick says.

He’s most proud though that he personally persuaded the council to convert a central car park into Queenstown’s Village Green and develop the waterfront. The schist stone wall - historical poem etched in, has since starred in thousands of international holiday snapshots.

It’s all quite an achievement for the young Auckland Grammar kid who was told ‘teacher or lawyer’ was it. “We had 10 minutes each and the careers advisor said, “So you want to be a teacher? I said, ‘No way!’ “Well, the only other thing you can do is be a lawyer, which I’d never thought about so I said, ’Ok’. All done in five minutes,” Warwick grins.

He changed primary schools every few years, as the son of a bank manager, from Wellington to Fiji, Winton, Tuakau, Maungaturoto and Warkworth. His ex-headmistress mum was into speech and drama and after a debut as a jester in a Shakespeare play, Warwick gained the confidence he needed to endure five years of boarding school jibes. “Boarding schools were rough back then, especially when you were a year younger, smaller, smarter, wore glasses and weren’t good at sport, but it teaches you life.”

At uni he survived Capping Week homebuilt raft races on Auckland Harbour, drowning students rescued by the Coastguard. His Air NZ uni holiday job became fulltime for 18 months – Warwick and his mates onto the 90% airfare discount on travel.

After a trip to Peru, where he met a Dutch girl, it was off on a three-and-a-half -year OE, hitch hiking around Europe and Scandinavia, working in bars. “I watched the 1981 Springbok-All Blacks game in South Africa during six months in Africa.” Big money on Perth oil exploration got him home ready to buy a suit and car and find a lawyer job. “I was five years out of Law School and hadn’t looked at a law book since I graduated.”

He bought his mother’s Triumph 2000 and got the suit, but no job, hitching to Queenstown to see a mate. “Bored one day I called on the two local law firms to practise interviewing in my travel jeans, hair to my breastbone and a beard.”

Walter Rutherford had been advertising to no avail, so Warwick was in, thrown in the deep end with a huge variety of work which he loved. “As duty solicitor for court I had to take turns advising mostly junior crims. I didn’t know what I was doing and I was terrified of Judge (Joe) Anderson.”

A weekend parachute course and solo jump left him “10-feet tall and bulletproof” on Monday in court. “I was still buzzing and looked Judge Anderson right in the eye.”

The next argument he had to win became his wife when Warwick was sent to meet American developer Ted Topolski, who planned a restaurant at Waterfall Park. “He sent me to meet his architect, who I’d never heard of, and we had a blistering argument for 45 minutes as she was a real greenie and I acted for developers.”

Tanganyika-born Brit Jackie Gillies canned her return to England, and they married in 1992. “Jackie is commonly known as the small steamroller,” Warwick grins. “We’ve continued debating but you get out of her way.”

They lived in a cottage at Lake Johnson with two babies while renovating the original Hansen homestead – Jackie’s passion as a heritage architect, through Queenstown’s coldest winter in 30 years.

Semi-retiring to Auckland’s Devonport in 2022 Warwick still works two days a week remotely for Queenstown developer Chris Meehan on the Ayrburn consents, and Queenstown’s new film studio.

He also only resigned from his six-year voluntary role as a Queenstown Trails Trust trustee in 2022, spending a year on the consents for the new Arrowtown-Arthurs Point-Tucker Beach Trail.

They’ve now bought a Devonport villa, which Jackie’s doing up, so there’s no retiring yet: “I spent today staining fences,” he smiles.