Debbie Swain-Rewi - Supermum of six - Paying it forward

Debbie Swain-Rewi’s life may have been an emotional rollercoaster that could’ve tipped many over the edge. Instead, it built resilience and instilled immense gratitude and compassion in a heart that’s still constantly pouring out to others.

Born in Wellington to the teenage daughter of a Railway worker and adopted by a Blenheim optometrist and his wife, Debbie’s adoptive mother died in a boating tragedy when she was two.

Her father, a hemophiliac, was her idol. “I couldn’t sit on his knee because of the bleeding so I’d stand beside his dining chair so he could hug me, and he’d read stories, and we’d watch TV.”

Debbie’s dad owned three local optometry practices and her Nana moved in to care for her after her mum died.

Sadly, her father died when she was 12, two years after remarrying. “The greatest lesson he taught me was to be grateful and never feel sorry for myself, to look outward and not inward.”

At 13 Debbie’s stepmother sent her to St Bride’s boarding school in Masterton.

After nurse aiding, she started enrolled nurse training in Nelson, including at a psychiatric and psychopaedic hospital.

During seven years at Picton Hospital the nurses became accustomed to pushing the old Dodge ambulance to get it started.

Debbie cashed in some of her father’s shares at 21 and did a solo 13-week trip around Europe where she experienced her ‘first great love” - an American, igniting a lifelong passion for travel.

Back in Picton, Debbie’s early political activist tendencies were emerging at 21, and she became local rep, and then national chairperson of the Enrolled Nurse’s Section of the NZ Nurses Association, also becoming Marlborough Branch chairperson,

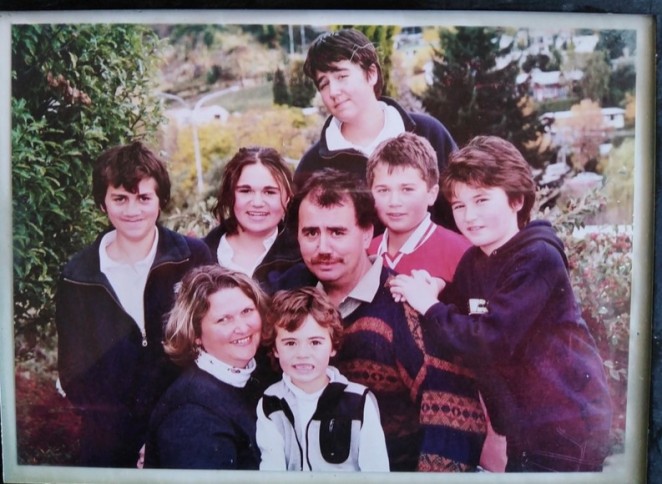

While chairing a conference in Invercargill in 1985 she met husband of 37 years Darren, marrying him the following year.

Soon pregnant with Grant, life was a constant juggle with Debbie working at Southland Hospital. Baby Newton arrived 16 months later, born with a severe cleft palate that required surgeries until he was 22. She says she always wanted a big family and six weeks after Newton’s birth, she was deliberately pregnant with Vivian.

Newton’s condition launched her into the emotional trail of finding her birth parents. “I assumed my kids would want to know if it was hereditary, but they never have.”

Despite being vocally opposed to the point of calling National Radio’s George Balani nighttime talkback show in the early 1980s to protest the new Adult Adoption Act, Debbie found herself signing all the forms. “The woman handed me my birth certificate and I folded it back into the envelope and into my bag. “I’d seen the name ‘Kathleen’ and decided I must be my Auntie Kathleen’s child. I thought, ‘I’m not opening that can of worms’.” However, her birth mother had named her ‘Kathleen’.

In 1990 Debbie met both of her birth parents, then her three full sisters and brother. “It was weirdly familiar. I’d studied psychology through Massey – nature and nurture. My sisters all sat the same way as me and we even had similar handwriting.” Two years later she and one sister had babies on the same day.

By now they’d moved to Queenstown, Michael born soon after. Pene arrived two years later, followed by Thomas.

Rent was $300 a week and there was no supermarket, so Debbie worked full-time as opening night manager at the Millennium Hotel. Weeks later she scored a job at Lakes District Hospital. She’d work Sunday night to Thursday on hotel nightshifts and three days at the hospital, with six kids.

When the first weekend trans-Tasman flights arrived, she worked as a Customs officer too. After a stint at the Heritage, Debbie worked nights fulltime at the hospital “to be available for anything going on at school”.

In her early 40s she also studied, commuting to Invercargill and gaining her Registered Nursing Degree, and Postgrad Diploma.

This led to occupational health and launching her Mobile Industrial Health workplace health and safety business.

She also worked part-time for Nga Kete on its Glenorchy Health Clinic. Funding ended eight years ago, and Debbie has continued this service voluntarily ever since. Debbie started a Wahine Ora (Women’s Health) group to improve health outcomes locally for Māori and worked as a smoking cessation coach.

Last year she was a finalist in the Otago Inspirational Women Awards and has been a finalist twice in the Heart of the District Awards.

Despite the challenges, the hardest thing she’s faced was Vivian’s cervical cancer diagnosis, aged just 28, and given a 30% chance of survival. Vivian fought courageously, running the Honolulu Marathon seven months after her treatment.

About 12 years ago, and again during Vivian’s diagnosis, Debbie says she became acutely aware of racist attitudes towards Māori, and her kids, becoming a strong advocate for Māori health, developing the Te Whare Hauora Trust locally.

“Thanks to my kids’ experiences I now have immense empathy for Māori,” she says.