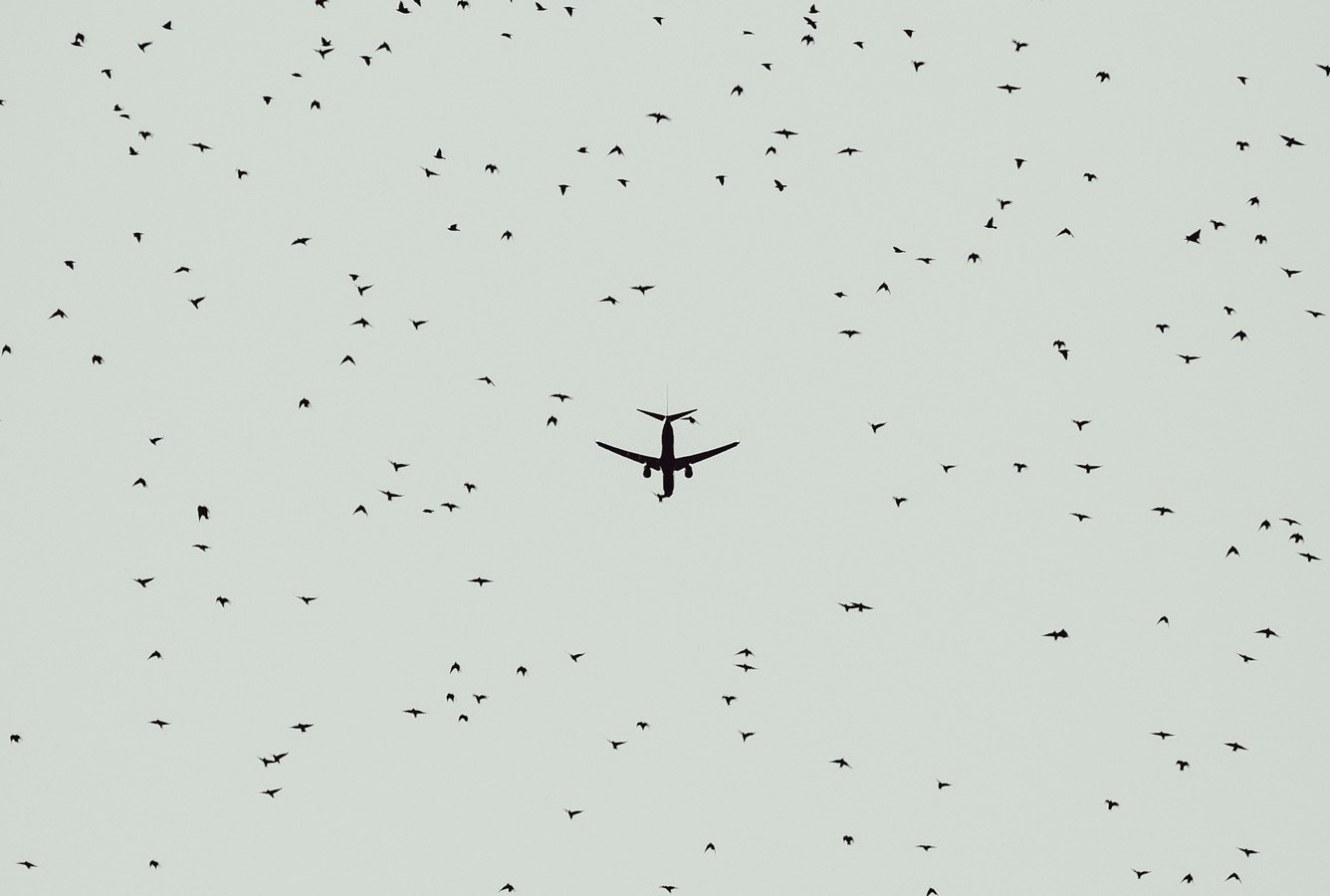

Collisions between planes and birds follow seasonal patterns and overlap with breeding and migration – new research

Tirth Vaishnav, PhD Candidate in Ecology and Biodiversity, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, writing for The Conversation NZ

Bird strikes with aircraft pose a serious threat to human safety. The problem dates back to the early days of aviation, with the first death of a pilot recorded in 1912 when an aircraft crashed into the sea after striking a gull.

Since then, 795 lives have been lost to collisions between aircraft and birds, not to mention the countless bird fatalities.

As aircraft get faster, quieter, larger and more numerous, the risk of serious accidents increases accordingly. Every year, the aviation industry incurs damages worth billions of dollars.

To mitigate this problem, airports around the world implement wildlife hazard management, including dispersing flocks away from the runway, tracking local bird movements and managing potential food sources such as landfills and farms near the aerodrome.

In our recent study, we zoomed out from the local airport and examined seasonal and hemispheric trends in bird strikes.

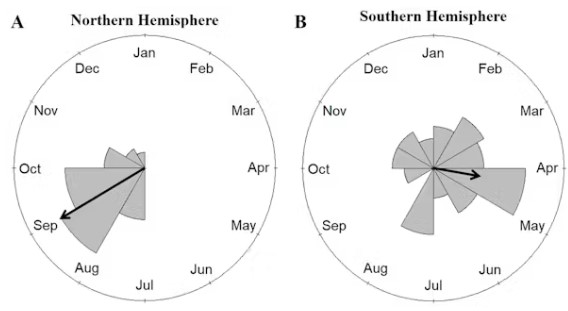

We found they peak in late summer and autumn in both hemispheres, but the annual distribution differs between the northern and southern hemispheres. Seasonal trends in bird strikes were seemingly influenced by avian breeding and migration patterns.

Seasonal patterns

To assess seasonal patterns in bird strikes, we gathered information for individual airports from existing literature and online sources. Our dataset includes 122 airports in 16 countries and five continents.

For each hemisphere, we determined the time of year with the overall highest number of bird strikes and the spread of strikes through the year.

We found that bird strikes peaked in late August in the northern hemisphere and in early April in the southern hemisphere. Strikes were relatively more seasonal in the north, while they had a greater annual spread in the south.

For instance, strikes in New York or Oslo in the northern hemisphere were considerably higher in August compared to other times of the year, while in Wellington or Durban in the southern hemisphere, strikes occurred more.

Birds strikes are more seasonal in the northern hemisphere and more distributed across the year in the southern hemisphere. Author provided, CC BY-SA

Bird strikes peaked in the autumn season in each hemisphere. Autumn is generally when young birds fledge and take to the skies. There may be two explanations for why bird strikes are higher during this time of year.

- For young birds, avoiding foreign objects in the flight path may be a learned behaviour. This would result in juveniles being struck at a higher rate.

- The greater number of birds in the air during autumn due to the influx of fledglings may result in more strikes, with adults and juveniles being struck at random.

Links to bird migration

Seasonal peaks in bird strikes were more pronounced in the north compared to the south. Approximately 80% of the southern hemisphere’s surface is water and the solar energy absorbed by the oceans leads to a more stable thermal regime.

Conversely, the surface of the northern hemisphere is mostly land, leading to greater fluctuations in temperature. Birds migrate in response to these environmental factors and this influences global avian distributions and abundances.

The intensity of migration is, therefore, much stronger in the northern hemisphere compared to the southern hemisphere, where local bird abundances are more stable seasonally.

Our findings bridge a gap between aviation safety and macroecology. Airport authorities can use this information in several ways:

- Wildlife officers can optimise their bird strike mitigation efforts by allocating more resources in the autumn months, particularly in northern regions.

- Management plans for “problem” species such as gulls are often adapted from existing plans for similar species at other airports. Information on patterns in bird strikes may help in customising these plans to local bird behaviour.

- Bird strikes are a global issue, so better standardisation in reporting bird strike statistics could improve our ability to analyse them at a global scale.

Finally, with climate change altering the seasonal timing of cyclical events, such as avian breeding seasons and migration patterns, it may be crucial to forecast the impact of these changes on the seasonal trends in bird strikes.

To some degree, bird strikes may be inevitable. But with the cooperation of aviation authorities, scientists and policy makers, we may be able to minimise their frequency and intensity.